Introduction

Moksha, a profound concept in Hinduism, is often described as liberation or spiritual enlightenment. It represents the ultimate goal of human life, where the soul (atman) is freed from the cycle of birth and rebirth (samsara) and unites with the absolute reality (Brahman). Achieving moksha means breaking the bonds of worldly attachments, desires, and suffering, leading to a state of eternal bliss and inner peace.

Throughout Hindu philosophy, moksha holds a central place, representing the culmination of one’s spiritual journey. Different schools of thought within Hinduism propose various paths to attain moksha, ranging from selfless action and devotion to meditation and self-realization. This pursuit of liberation transcends mere religious practice, influencing ethical living, moral duty (dharma), and one’s relationship with the universe.

The concept of moksha is explored in depth across Hindu scriptures, particularly in the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Puranas, and the philosophy of Vedanta. Each of these texts provides unique perspectives on what moksha entails and the ways in which one can attain it. This blog delves into the treatment of moksha across these key scriptures, offering a comprehensive understanding of the spiritual pursuit that has shaped Hindu thought for millennia.

Moksha in the Vedic Period and Texts

Introduction to the Vedic Texts

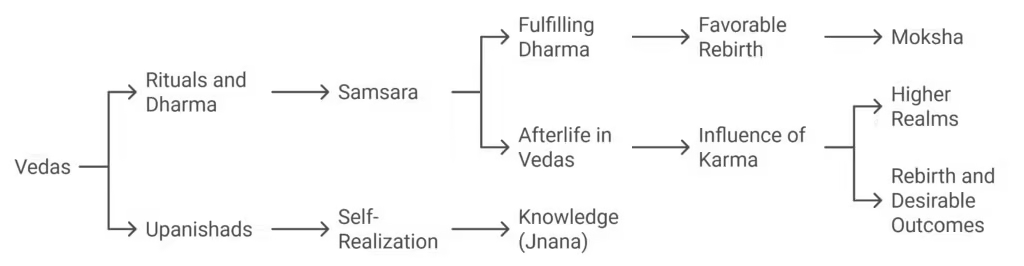

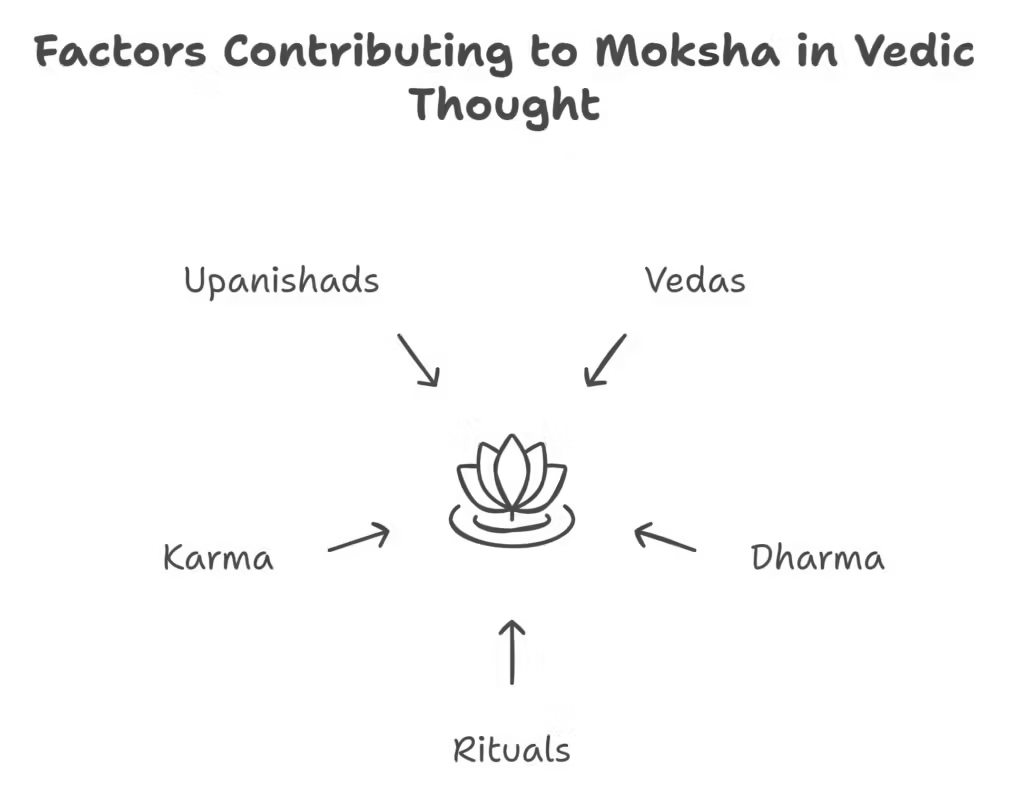

The Vedas, considered the oldest and most foundational scriptures of Hinduism, form the bedrock of early Hindu philosophy. Composed of hymns, rituals, and spiritual teachings, they focus on maintaining cosmic order through rituals and offerings. While the Vedic texts primarily address rituals and the pursuit of material and social harmony, the seeds of moksha, or spiritual liberation, are subtly embedded within their verses.

In the Vedic period, moksha was not as explicitly articulated as in later scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita or the Puranas. The Vedas placed more emphasis on living in accordance with dharma (righteous duty) and fulfilling one’s role in society. However, the concept of transcending worldly existence and escaping the cycle of life and death is present, albeit in a more implicit and ritualistic form.

Moksha in the Vedic Period

In early Vedic thought, the idea of liberation was closely linked to samsara—the perpetual cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Liberation from this cycle, or moksha, was seen as an indirect outcome of fulfilling one’s dharma. By performing the prescribed rituals and duties according to one’s caste and stage of life, individuals aimed for a favorable rebirth, which would bring them closer to liberation over successive lifetimes.

During this period, moksha was intertwined with the idea of maintaining cosmic balance through ritual, and while direct discussions of moksha were rare, the ultimate goal of escaping samsara and achieving spiritual liberation was a developing concept.

Afterlife in the Vedas

The Vedic texts offer glimpses into the early Hindu views of the afterlife. While they do not provide a comprehensive description of what happens after death, there are references to various realms where souls may reside based on their accumulated karma (actions). One such realm is pitrloka, the world of the ancestors, where the virtuous dead are believed to dwell.

The Vedas suggest that the afterlife is influenced by the performance of rituals and one’s adherence to their societal duties. Souls who have accumulated good karma through virtuous living are rewarded with higher realms, while those who have incurred negative karma face rebirth or less desirable outcomes. Although the Vedic focus is more on maintaining order in this life, these references to the afterlife hint at the early stages of the Hindu understanding of moksha.

Concept and Stages of Moksha in Vedic Thought

In Vedic thought, the ultimate liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth was associated with returning to a state of completeness or wholeness, referred to as Bhuma. This state is devoid of suffering, where the dualities of existence—such as life and death, joy and sorrow—cease to exist. Moksha in this context is not just the cessation of rebirth, but the dissolution of individual identity into a greater, undivided reality.

As Vedic philosophy evolved, particularly in the later Upanishads (which form the concluding part of Vedic literature), the path to moksha began to emphasize jnana (knowledge). The Upanishads introduced the idea that self-realization—understanding the oneness of the atman (individual soul) with Brahman (the ultimate reality)—was the key to liberation. This philosophical shift laid the groundwork for later Hindu thought, where knowledge, meditation, and inner inquiry became central to the pursuit of moksha.

Moksha in the Bhagavad Gita

Overview of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita, often referred to as the Gita, occupies a central place in Hindu philosophy as a profound spiritual and philosophical guide. Comprising 700 verses, it forms a key section of the epic Mahabharata, where Lord Krishna imparts timeless wisdom to the warrior prince Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra.

The Gita addresses life’s most fundamental questions and provides a comprehensive blueprint for leading a spiritually fulfilling life. Among its many teachings, the concept of moksha stands out as the ultimate goal of human existence—liberation from the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth, and the realization of one’s eternal nature.

In the Bhagavad Gita, moksha is described as the liberation of the soul (atman) from material bondage and the realization of its eternal, divine nature. Krishna emphasizes that moksha is the state where the soul is no longer entangled in the cycle of samsara, characterized by suffering, desires, and attachments.

Liberation comes through understanding one’s true self, which is beyond the physical body and mind. According to the Gita, moksha is not just about escaping worldly existence but about attaining spiritual knowledge that leads to unity with the supreme reality.

Three Paths to Moksha in the Gita

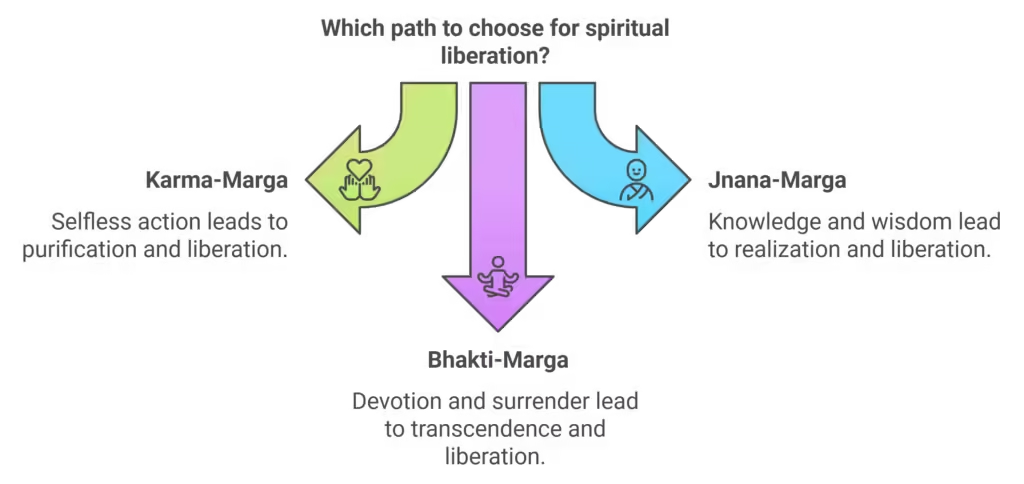

The Bhagavad Gita presents three distinct yet interconnected paths to moksha, acknowledging that individuals have different temperaments and inclinations. These paths offer multiple ways to reach liberation:

- Karma-Marga (Path of Selfless Action): This path emphasizes performing one’s duties without attachment to the results. By acting selflessly, with dedication and a sense of service to others, an individual purifies the mind and heart, paving the way for spiritual freedom. Krishna urges Arjuna to perform his warrior duties without concern for success or failure, teaching that detachment from outcomes leads to inner liberation.

- Jnana-Marga (Path of Knowledge and Wisdom): The path of knowledge involves deep contemplation on the nature of reality and the self. Through jnana (spiritual wisdom), one realizes the non-duality between the self (atman) and the supreme reality (Brahman). This realization dispels ignorance (avidya), which is the root of bondage. Jnana-Marga is an intellectual and introspective journey to understanding the eternal truth and achieving moksha through knowledge of the self.

- Bhakti-Marga (Path of Devotion): The path of devotion is marked by love, faith, and complete surrender to God. Bhakti, or devotion, is considered one of the most accessible and powerful paths in the Gita, especially in the age of Kali Yuga. By developing a personal and emotional connection with God, and offering one’s thoughts, actions, and emotions to the divine, an individual transcends ego and material desires, moving toward liberation.

Key Concepts: Mukti and Krishna’s Role

The Bhagavad Gita also touches upon the concept of mukti, which is often used interchangeably with moksha but carries subtle distinctions. Mukti refers to freedom from suffering and worldly attachments, while moksha implies a more profound, final liberation—union with the divine.

Krishna’s role in the Gita is both that of a teacher and an embodiment of the divine. He reveals to Arjuna the path to moksha, guiding him to overcome doubt and fear, and to embrace his higher spiritual calling. Krishna represents the ultimate reality and serves as the means by which Arjuna, and all seekers, can attain liberation. Through surrendering to Krishna, one is said to attain eternal freedom from the cycles of birth and death.

While Arjuna does not achieve moksha within the narrative, the wisdom Krishna imparts sets him on a transformative spiritual path. Krishna himself, being an incarnation of Vishnu, embodies moksha and does not seek it in the human sense.

Challenges in Achieving Moksha in Kali Yuga

According to Hindu scriptures, attaining moksha in the current age of Kali Yuga—the age of darkness and moral decline—is more challenging due to increased distractions, desires, and materialism. However, the Bhagavad Gita offers solace by stating that the path of bhakti (devotion) is especially accessible in Kali Yuga. Sincere devotion to God, through prayer, surrender, and love, can help overcome the spiritual challenges posed by this age and lead one to liberation.

Moksha in the Puranas

Introduction to the Puranas

The Puranas, a genre of ancient Hindu texts, serve as expansive narratives that blend mythology, history, and spiritual teachings. While the Vedas and Upanishads focus more on abstract philosophical ideas, the Puranas provide a more accessible, narrative-based approach to Hindu theology and cosmology. These texts play a crucial role in shaping Hindu beliefs and practices, including the understanding of moksha. The Puranas offer rich, illustrative stories about gods, goddesses, and sages, weaving in moral lessons and practical guidance on achieving liberation.

Moksha in the Puranic Tradition

In the Puranas, moksha is described as liberation from the cycle of samsara, much like in earlier texts. However, the Puranic tradition places a significant emphasis on both ritualistic practices and moral conduct as essential to attaining moksha. Through devotion, the performance of prescribed rituals, and leading a life aligned with dharma, an individual can purify the soul and ultimately transcend material existence.

The Puranas reinforce the idea that moksha is not just about intellectual or philosophical realization but also about living a righteous life, performing one’s duties, and maintaining a strong connection with the divine.

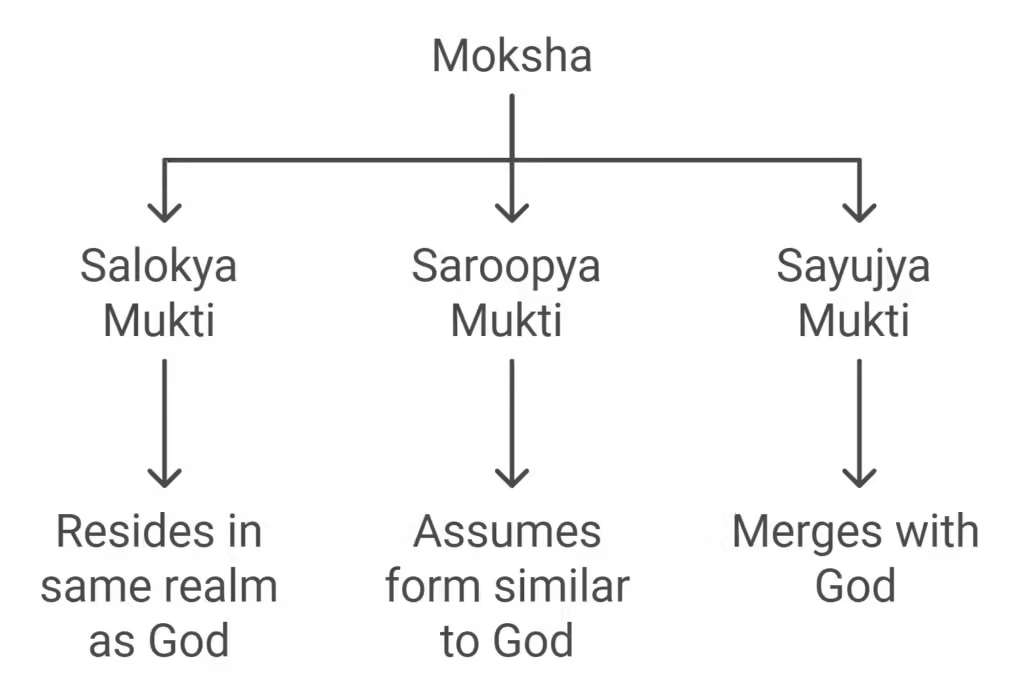

Types of Moksha in the Puranas

The Puranas elaborate on various forms of moksha, offering a more detailed categorization of liberation:

- Salokya Mukti: The soul resides in the same realm as God, living near the divine and enjoying divine presence.

- Saroopya Mukti: The soul assumes a form similar to God, reflecting the divine attributes and qualities.

- Sayujya Mukti: The soul merges with God, losing all individual identity and becoming one with the divine. This is considered the highest form of liberation.

The Garuda Purana, in particular, offers a deep discussion on the nature of moksha and the rituals that can assist in achieving it. It outlines post-death rituals aimed at helping the soul attain liberation, emphasizing the importance of both life choices and death rites in the soul’s journey toward moksha.

Mahabharata’s Contribution to Moksha

The Mahabharata, another epic text that includes the Bhagavad Gita, also contributes significantly to the understanding of moksha. Through the lives of its characters, the Mahabharata demonstrates how righteousness (dharma) and self-realization are crucial in the pursuit of liberation. The epic suggests that true moksha can only be attained through a combination of moral integrity, selfless action, and deep spiritual awareness. By illustrating the consequences of both virtuous and immoral behavior, the Mahabharata reinforces that self-realization and ethical living are key to escaping the cycle of samsara.

Moksha in Advaita Vedanta

Introduction to Advaita Vedanta

Advaita Vedanta, one of the most prominent schools of Hindu philosophy, is rooted in the concept of non-duality (advaita), which asserts that the ultimate reality, Brahman, and the individual soul, atman, are not separate entities but are one and the same. This philosophy was systematically expounded by Adi Shankaracharya in the 8th century CE, and it profoundly reshaped Hindu thought.

In the context of moksha, Advaita Vedanta offers a unique and abstract approach: liberation is not about traveling to a different realm or achieving something external but realizing that one’s true self (atman) is already identical with the ultimate reality (Brahman). The journey to moksha is thus a journey inward, aimed at dispelling ignorance and recognizing the fundamental unity of all existence.

Definition of Moksha in Advaita Vedanta

In Advaita Vedanta, moksha is defined as the realization that the individual self (atman) and the universal self (Brahman) are one. This non-dualistic understanding means that liberation is not something to be attained or reached but a state of being that already exists. The problem, according to Advaita Vedanta, lies in avidya (ignorance), which creates the illusion of separateness between the self and the supreme reality.

Moksha, therefore, is the direct experience of this unity, where the illusion of individuality dissolves, and one realizes the oneness of all existence. This state of self-realization leads to ultimate freedom from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara), and the realization of the soul’s eternal, changeless nature.

Attainment of Moksha in Advaita Vedanta

The path to moksha in Advaita Vedanta is primarily through jnana (self-inquiry or knowledge). This philosophical inquiry involves deep reflection on the nature of the self and reality, often encapsulated in the famous phrase, tat tvam asi (That thou art), which emphasizes the identity of the individual soul with the universal reality. By continuously meditating on the oneness of atman and Brahman, one gradually overcomes avidya (ignorance) and attains liberation.

Central to this process is the dissolution of the ego and the realization that the body, mind, and senses are transient and not the true self. Through practices like meditation, contemplation, and scriptural study, the seeker gradually moves toward self-realization, where the boundaries of the self and the universe fade away, leaving only the undifferentiated Brahman.

Stages of Moksha

Advaita Vedanta outlines two key stages of moksha:

- Jivanmukti (Liberation while living): This is the state of being liberated while still in the physical body. A jivanmukta is someone who has realized the oneness of atman and Brahman and is no longer bound by ego, desires, or the illusions of the material world. Despite continuing to live a normal life, the jivanmukta experiences inner freedom, is unaffected by suffering or pleasure, and is free from the cycle of karma. This stage represents the highest achievement of spiritual practice.

- Videhamukti (Liberation after death): Videhamukti refers to the liberation that occurs after the physical body has died. In this state, the soul, having already realized its oneness with Brahman during life, fully merges with the ultimate reality. There is no further rebirth, and the soul exists in a state of eternal unity with the divine.

Philosophical and Practical Aspects of Moksha

The Four Pillars of Moksha (Purusharthas)

In Hindu philosophy, life’s goals are structured around four purusharthas—dharma (righteousness), artha (material prosperity), kama (desire or pleasure), and moksha (liberation). These pillars represent a holistic approach to life, where moksha stands as the ultimate goal.

The purusharthas provide a balanced framework for human existence, ensuring that while one pursues material success and pleasure, they remain aligned with ethical values and spiritual growth. Moksha, as the final aim, transcends the other three and offers liberation from the temporal world, guiding the individual toward eternal bliss.

Three Types of Moksha According to the Upanishads

The Upanishads, considered the philosophical heart of the Vedas, offer three distinct approaches to attaining moksha:

- Karma Mukti (Liberation through Action): In this approach, liberation is achieved through the selfless performance of one’s duties (karma). When actions are done without attachment to results, they purify the heart and lead to spiritual progress.

- Jnana Mukti (Liberation through Knowledge): This is the path of wisdom, where moksha is attained by realizing the ultimate truth of non-duality, through deep meditation, contemplation, and knowledge of the self.

- Bhakti Mukti (Liberation through Devotion): This path emphasizes love and devotion to God as the means to liberation. By surrendering completely to a personal deity, an individual transcends ego and realizes unity with the divine.

Virtues and Jewels of Moksha

In Hindu philosophy, certain virtues are considered essential for the attainment of moksha. These virtues are often referred to as the “jewels” of spiritual life and include:

- Compassion: The ability to empathize with others and act kindly.

- Wisdom: Insight into the true nature of reality and self.

- Detachment: The ability to remain unaffected by material desires and outcomes.

- Truthfulness: Aligning speech and action with universal truth.

These virtues purify the mind and heart, preparing the soul for the ultimate realization of moksha.

Highest Form of Moksha

Among the various types of moksha, Sayujya Mukti is often regarded as the highest form. In this state, the individual soul merges completely with Brahman, losing all sense of individuality and becoming one with the supreme reality. This ultimate union with Brahman represents the dissolution of all dualities and the end of the cycle of samsara. In Sayujya Mukti, the soul experiences eternal bliss and freedom, as it is no longer separate from the divine essence.

This highest form of moksha is celebrated in Hindu philosophy as the pinnacle of spiritual achievement, where the seeker not only transcends worldly existence but becomes one with the source of all existence, attaining eternal peace and liberation.

Conclusion

The concept of moksha, while central to Hindu philosophy, is treated with varying depth and nuance across the different scriptures. The Vedas, as the earliest texts, touch on moksha more indirectly, framing it within the context of performing one’s duties to escape the cycle of samsara. The Bhagavad Gita expands this notion, presenting moksha as liberation from material bondage and offering three distinct paths—karma (selfless action), jnana (knowledge), and bhakti (devotion)—to attain it.

The Puranas provide more narrative-driven perspectives on moksha, often emphasizing ritual practices and moral living as key to achieving liberation. In contrast, Advaita Vedanta takes a more philosophical approach, advocating for moksha as the realization of non-duality between atman and Brahman, focusing on self-inquiry and knowledge as the primary means to liberation.

Moksha remains the ultimate spiritual goal in Hinduism, representing the soul’s release from the endless cycle of birth and death and its union with the divine. Whether approached through duty, knowledge, or devotion, the pursuit of moksha guides the individual toward a higher understanding of self and the universe.

As readers reflect on these diverse interpretations, they are encouraged to explore the path that resonates most with their own spiritual inclinations, whether it be through action, intellectual inquiry, or heartfelt devotion. The pursuit of moksha is deeply personal, yet universally significant as it symbolizes the transcendence of the soul beyond the material world.

For readers interested in delving deeper into the concept of moksha and its various interpretations, the following resources are recommended:

- Study.com – Moksha in Hinduism: Definition & Lesson Quiz

- New Indian Express – Moksha is Well-Defined in Gita

- Exotic India Art – Moksha

- LinkedIn – Discovering Life’s Purpose: Your Guide to the Four Pillars

- Wikipedia – Moksha

- ISKCON Dwarka – Blog on Moksha

- Emoha – Life Lessons from the Garuda Purana

- Moksh.life – What is Moksha?

- Reddit – Vedic Thoughts on the Afterlife